HUMANITY

DEFINING

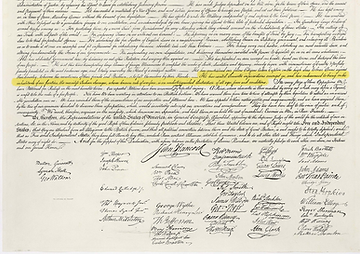

U.S. Declaration of Independence

Declaration of Independence (1819); By John Trumbull - US Capitol, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=180069

Adopted on July 4, 1776, the Declaration of Independence stands as one of the most influential political documents in modern history. While its immediate purpose was to justify separation from Great Britain, the Declaration is also a philosophical statement grounded in natural law theory, articulating a vision of human equality, inherent rights, and the moral limits of government power. It asserts that certain rights exist prior to government and that political authority is legitimate only insofar as it secures those rights.

At the core of the Declaration is its assertion that human rights are inherent rather than conferred by political authority. The document famously proclaims:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

By identifying life as one of the unalienable rights, the Declaration affirms that it is not granted by government but recognized as pre-existing political institutions. Within the natural rights framework shared by many Enlightenment thinkers, life is understood as a fundamental condition for the exercise of liberty and the pursuit of happiness, both of which presuppose continued existence.

The Declaration grounds human rights in a source beyond human law by stating that individuals are “endowed by their Creator.” This language reflects the Founders’ reliance on natural law concepts rather than mere social convention. Under this framework, rights do not originate from governments, and political authority is limited in scope. While the Declaration does not define the full implications of this dignity, it clearly rejects the idea that rights depend solely on legislative will.

The document further defines the moral purpose of government, stating:

That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.

Here, the protection of unalienable rights, including life, is presented as the justification for political authority. When government becomes destructive of these ends, the Declaration argues that it loses its legitimacy. This principle is illustrated in the list of grievances against the British Crown, including accusations of violence and destruction that violated the security of the population. One such grievance condemns warfare that resulted in indiscriminate loss of life:

He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

Although the phrase “sanctity of life” does not appear in the Declaration, the document clearly treats life as an unalienable right that governments are morally bound to secure. By affirming human equality, grounding rights beyond political authority, and condemning arbitrary destruction of life, the Declaration establishes a moral framework in which human life is not subject to governmental permission, but stands as a foundational limit on political power.

The 1823 facsimile of Timothy Matlack's engrossed copy of the Declaration of Independence; By original: w:Second Continental Congress; reproduction: William Stone - numerous, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=621811

English Common Law Tradition

The English Common Law tradition treated the preservation of human life as a central aim of law and justice. In its constitutional inheritance, Magna Carta (1215) is best understood not as a philosophical treatise on the sanctity of life, but as a foundational restraint on arbitrary power. It declares: “No free man shall be seized or imprisoned… except by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land.” (Magna Carta, 1215, cl. 39) This principle of due process mattered because it assumed the state must justify any act that could deprive a person of liberty or life under established law.

Magna Carta (1215); British Library, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Eighteenth-century jurist Sir William Blackstone articulated this commitment more explicitly by grounding Common Law in natural law. He wrote that “the law of nature… dictated by God himself, is of course superior in obligation to any other.” (Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England, Book I, ch. 2, 1765) Within this framework, Blackstone identified life as the first object of legal protection, stating: “The right of personal security consists in a person’s legal and uninterrupted enjoyment of his life, his limbs, his body, his health, and his reputation.” (Blackstone, Commentaries, Book I, ch. 1, 1765) In this tradition, life was understood as the foundational right upon which all other liberties depend.

At the same time, English Common Law approached unborn life with legal nuance. Blackstone acknowledged that “an infant in ventre sa mère is supposed in law to be born for many purposes,” particularly in matters such as inheritance and civil protection. (Blackstone, Commentaries, Book I, ch. 16, 1765) However, criminal law historically followed the “born alive” rule, meaning homicide charges generally applied only if a child was born alive and then died from injury. This distinction is essential for accuracy: while Common Law affirmed life as a fundamental legal good, prenatal recognition existed primarily in limited civil contexts rather than as full criminal homicide protection.

Natural Law Theory

Natural Law Theory maintains that moral truths are not created by governments or societies but are rooted in human nature itself and discoverable through reason. From its earliest classical formulations, natural law has consistently identified human life as a fundamental moral good. The Roman philosopher Cicero articulated this principle with enduring clarity, writing: “True law is right reason in agreement with nature; it is of universal application, unchanging and everlasting” (Cicero, De re publica 3.22).

Because natural law is grounded in reason and nature rather than convention, it establishes moral limits on human authority, including the obligation to respect and protect innocent human life.

This moral framework is further developed in the medieval philosophy of Thomas Aquinas, whose account of natural law remains foundational. In Summa Theologiae, Aquinas teaches that the first principle of moral reasoning is self-evident: “good is to be done and pursued, and evil is to be avoided” (Aquinas, Summa Theologiae I–II, q.94, a.2). From this principle flow specific moral precepts grounded in human inclinations, including the inclination toward self-preservation. Aquinas explains that human beings naturally seek to preserve their own existence, and therefore actions that sustain life belong to the natural law, while acts that directly destroy innocent life contradict it. Within this framework, the protection of life is not merely one value among many but a foundational good upon which all other human goods depend.

Natural law theory also profoundly shaped the Anglo-American legal tradition. Sir William Blackstone, whose Commentaries on the Laws of England deeply influenced early American jurisprudence, affirmed the supremacy of natural law over human legislation, stating: “This law of nature, being coeval with mankind and dictated by God himself, is of course superior in obligation to any other.” He concluded unequivocally that “no human laws are of any validity, if contrary to this.” (Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England, bk. 1, introd., sec. 2). In the natural law tradition, the sanctity of human life stands as a moral constant: a universal good recognized by reason, affirmed across centuries, and understood as a limit that no government or legal system may justly transgress.

Saint Thomas Aquinas. Origin: Antwerp. Date: 1620 – 1668. Object ID: RP-P-OB-23.852. Credit: Rijksmuseum, public domain.

Christian Belief (Imago Dei)

Within the Christian tradition, the sanctity of human life is grounded in the doctrine of Imago Dei—the belief that human beings are created in the image of God. This concept is introduced in the opening chapter of Genesis, where humanity’s creation is presented as unique within the created order: “So God created man in his own image; he created him in the image of God; he created them male and female” (Gen. 1:27, NRSV). In contrast to plants and animals, human beings are explicitly identified as image-bearers of God, a designation that Jewish and Christian theologians have historically understood to confer inherent dignity, moral worth, and relational responsibility. Human value, within this framework, is not contingent upon physical development, functional capacity, or social status, but is rooted in divine authorship.

The ethical implications of Imago Dei extend across the whole of human life. Scripture explicitly connects the prohibition against the unjust taking of human life to humanity’s creation in God’s image: “Whoever sheds human blood, by humans his blood will be shed, for God made humans in his image” (Gen. 9:6, NRSV). Biblical poetry further portrays God as actively involved in human formation before birth: “For it was you who created my inward parts; you knit me together in my mother’s womb” (Ps. 139:13, NRSV). Taken together, these texts form a consistent theological foundation within Christian belief that human life possesses intrinsic worth from its earliest stages, warranting moral protection and reverence irrespective of age, ability, or condition.

Islamic Beliefs

Islamic belief affirms the sanctity and inviolability of human life as a foundational moral principle grounded in divine revelation. The Qur’an consistently presents life as sacred because it is created by God and entrusted to humanity as a moral responsibility. In a passage recounting a principle given to the Children of Israel, the Qur’an states: “Whoever kills a soul unless for a soul or for corruption [done] in the land—it is as if he had slain mankind entirely. And whoever saves one—it is as if he had saved mankind entirely” (The Qur’an, trans. Sahih International, 5:32). Although this verse refers to an earlier divine law, Islamic scholars have long understood it as expressing a universal moral truth about the value of human life.

The Sultan Ahmed Mosque (Blue Mosque), built between 1609–1616 under Ottoman Sultan Ahmed I.

Islamic theology further teaches that life belongs ultimately to God, not to human beings or the state. The Qur’an commands: “Do not take life, which God has made sacred, except in justice” (The Qur’an, trans. Sahih International, 17:33), affirming that human life possesses inherent sanctity (ḥurmat al-ḥayāh). Classical Islamic jurists interpreted this principle as placing strict moral limits on the taking of innocent life and grounding ethical obligations to preserve life wherever possible. While Islamic legal tradition contains detailed discussions about moral responsibility at various stages of human development, there is broad agreement that unjust harm to innocent life constitutes a grave violation of divine law and human dignity.

Human Dignity Philosophy (Kant)

Painting by Christoph Wetzel (2000). Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), German philosopher of the Enlightenment, among other things a professor of logic and metaphysics in Königsberg.

Christoph Wetzel, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Immanuel Kant’s moral philosophy provides one of the most influential secular foundations for the concept of human dignity and the inherent worth of human life. Central to Kant’s ethics is the conviction that human beings possess an intrinsic value that is not dependent on usefulness, social status, or external evaluation. In Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (1785), Kant distinguishes between things that can be valued instrumentally and persons who possess an incomparable moral worth: “That which has a price can be replaced by something else as its equivalent; that which is above all price, and therefore admits of no equivalent, has a dignity” (Kant 1785, 4:434). Human life, within this framework, is not interchangeable or subject to trade-offs, but possesses a value that transcends calculation.

For Kant, this dignity arises from humanity’s moral status rather than from any particular capacity or social role. He grounds dignity in the principle that human beings must always be regarded as ends in themselves. As Kant famously formulates the moral law: “So act that you use humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, always at the same time as an end, never merely as a means” (Kant 1785, 4:429). This principle establishes a categorical moral boundary against treating human beings as expendable or subordinate to external goals. Within Kantian moral philosophy, respect for human life flows from the obligation to honor the inherent dignity of every human being, affirming that human worth is intrinsic, inviolable, and not subject to conditional valuation.

Disability & Vulnerability Ethics

Disability and vulnerability ethics challenge moral frameworks that tie human worth to autonomy, productivity, or cognitive ability. Instead, these perspectives affirm that human dignity is inherent and equal, regardless of physical or mental capacity. Within this view, the sanctity of life does not depend on independence or perceived “quality of life,” but on the intrinsic value of the human person.

Philosopher Eva Feder Kittay emphasizes that dependence does not diminish moral worth, arguing that “the dependency of some does not diminish their moral worth; rather, it reveals the ethical obligations of those who stand in relations of care” (Eva Feder Kittay, Love’s Labor: Essays on Women, Equality, and Dependency, 1999). Her work in feminist and disability ethics highlights vulnerability and dependency as universal aspects of human life, not moral deficiencies.

Similarly, Martha Nussbaum critiques ethical standards that exclude people with disabilities from full moral consideration. She affirms that “the dignity of a human being is not conditional on productivity or normal functioning,” grounding human worth in personhood rather than capacity (Martha C. Nussbaum, Frontiers of Justice: Disability, Nationality, Species Membership, 2006). Her capabilities approach insists that justice requires societies to protect and support those who are most vulnerable, rather than marginalize them for failing to meet functional norms.

These ethical commitments are reflected in international human rights law. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities affirms that “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights,” explicitly rejecting hierarchies of human value based on disability, dependence, or impairment (United Nations, Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 2006).

Together, disability and vulnerability ethics reinforce the sanctity of life by rejecting ability-based measures of human worth. They insist that dignity is not earned or graded, but inherent, and that a just society is revealed not by how it treats the strong, but by how it safeguards the lives of the most vulnerable.

Biological Continuity of Human Life

Human embryology describes human life as a continuous biological process that begins at fertilization. Development does not occur through discrete biological transformations in which one kind of being becomes another, but rather as an uninterrupted progression of the same living organism over time. As the standard medical text The Developing Human: Clinically Oriented Embryology states, “Human development is a continuous process that begins when an oocyte (ovum) from a female is fertilized by a sperm (or spermatozoon) from a male” (Moore, Persaud, and Torchia 2016).

At fertilization, a new, genetically distinct human organism is formed, possessing its own complete human genome and initiating coordinated, internally directed development. Bruce Carlson explains in Human Embryology and Developmental Biology that at this point “the embryo now exists as a genetic unity,” indicating that biological individuality is established at conception rather than gradually acquired (Carlson 2014).

Embryology consistently treats the embryo as an organism in its earliest developmental stage, not as a non-human entity or merely a potential human. O’Rahilly and Müller, in Human Embryology and Teratology, affirm that “The embryo is a human being in the earliest stage of development,” clarifying that terms such as embryo and fetus denote phases of growth, not changes in biological identity (O’Rahilly and Müller 2001). As the same authors note elsewhere, “Development is a continuum that does not lend itself to arbitrary division” (O’Rahilly and Müller 2001).

Because human development proceeds without biological interruption from fertilization onward, science identifies no later point at which a new human organism begins. This principle of biological continuity challenges ethical distinctions based on size, level of development, or dependency, and supports the understanding that human life, once begun, persists as the same individual throughout all stages of growth and maturation.